|

| Image of Blythe Hiss, Senior Information Specialist at NCPAD |

Yoga has been noted to have many positive effects on the mind and the body. This article is a review of empirically based studies (not anecdotal) that looked at the effects of yoga on measures of physiological health in pain, autoimmune, immune, musculoskeletal, psychological, and neurological conditions. The articles included in the review focused on research that assessed the effects of yoga sessions comprised primarily of poses as opposed to sessions that were mainly targeting breathing exercises and meditation. It did recognize, though, that since yoga classes often include all three elements, the effects of the poses themselves are often hard to isolate.

According to this review, more recent research has shown that yoga has many positive effects on general components of fitness and health and several specific conditions, as outlined below.

General components of fitness and health that are positively impacted by participation in yoga:

- Balance

- Blood pressure

- Flexibility

- Heart rate

- Leg strength

- Running performance, leg muscle control, balance - Mindfulness

- Pulmonary measures

- Oxygen consumption, heart rate, breath volume, breath rate, antioxidants - Sleep

- Sleep efficiency, total sleep time, sleep onset latency, number of awakenings, sleep quality, deep/restorative sleep - Weight loss

- Food consumption, eating speed, food choices, body mass index (BMI), waist and hip circumference, fat-free mass, cholesterol, eating disorder symptoms

Specific conditions that are positively impacted by participation in yoga:

- Anxiety

- Asthma

- Quality of life, mood, symptoms, bronchodilator usage, peak expiratory flow rates - Breast cancer

- Anxiety, pain, fatigue, relaxation, quality of life - Coronary artery disease

- Cholesterol, angina episodes, body weight, triglycerides, revascularization procedures, lesion progression, cardiovascular endurance, immune effects - Depression

- Diabetes

- Blood glucose, heart rate, blood pressure, body mass index (BMI), anxiety, cholesterol, triglycerides, antioxidants, stress markers, energy levels - Headaches

- Migraine intensity and frequency, medication use - Hypertension

- Blood pressure, blood glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, well-being, quality of life - Job stress

- Low back pain

- Function, medication use, pain intensity, back flexibility - Lymphoma

- Sleep disturbances - Multiple sclerosis

- Fatigue - Osteoarthritis

- Pain, joint tenderness, range of motion, physical function - Pregnancy conditions

- Hypertension, pre-term labor, stress, vagal activity, labor pain, length of labor - Rheumatoid arthritis

- Pain, vitality, self-efficacy

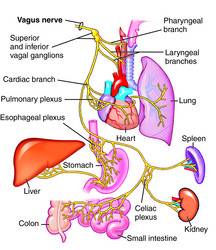

The many positive effects of yoga are considered to be related to the stimulation of pressure receptors under the skin (much like massage therapy), which causes an increase in vagal activity (see the image for more information on "vagal activity") and a decrease in cortisol, a primary stress hormone. This vagal activity has been reported after yoga but not after aerobic training in the same study. The model for these underlying mechanisms has not yet been tested, though components of it are supported by many of the studies in this review as well as by studies that the author herself has conducted. These components include:

- Massage therapy increases vagal activity.

- Yoga is considered a form of self-massage by rubbing limbs together as well as against the floor during poses. - Vagal activity decreases cortisol.

- Increased vagal activity and decreased cortisol are associated with decreased depression.

|

| Vagal activity is related to the vagus nerve, which is the tenth cranial nerve that originates in the brain stem and wanders all the way down to the colon. It supplies nerve fibers to the pharynx (throat), larynx (voice box), trachea (windpipe), lungs, heart, esophagus, and the intestinal tract. The vagus nerve also brings sensory information back to the brain from the ear, tongue, pharynx, and larynx. Image from: http://electricityitsallheart.blogspot.com/ |

The studies included in the review had the following limitations:

- Lack of randomization in several studies which potentially resulted in differences in baseline characteristics between groups

- People who are already motivated and perceive themselves as capable of participating in intensive yoga practices for a longer period of time may be over-represented in the samples due to self-selection

- Significant variability in the samples across studies, including sample selection and size

- Lack of good physical activity/attention control or comparison groups

- Dosage variability across studies (i.e., length or frequency of classes)

- Differences in the variables measured (outside of anxiety and stress) as well as the instruments used to measure these variables across studies. Physical effects (i.e., BMI), physiological effects (i.e., blood pressure), and biochemical changes (i.e., cortisol and other hormones) were all rarely measured.

- Often, gold-standard measures for specific conditions were not included

Given the vast amount of benefit that this review suggests could be obtained from practicing yoga poses and the many gaps that still exist in the body of literature, it seems that a call for more research is certainly in order. Perhaps if yoga were considered an effective exercise along with more traditional forms, both in the mainstream medical as well as general communities, research would develop and follow more specific protocols using more applicable outcome measures.

Resource:

Field, T. (September 7, 2010). Yoga clinical research review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. Retrieved December 6, 2010, from ( http://www.womenswaywmc.com/wp-content/uploads/Yoga.pdf).

Please send any questions or comments to Blythe Hiss at Blythe Hiss.